One year after California’s reopening, ‘wily’ COVID still stymies return to normal

One year after California’s reopening, ‘wily’ COVID still stymies return to normal San Francisco Chronicle

June 15, 2021, dawned cool and carefree across the Bay Area, where for the first time in well over a year, it finally looked like there might be a way out of the COVID-19 pandemic — and it might not be too far off.

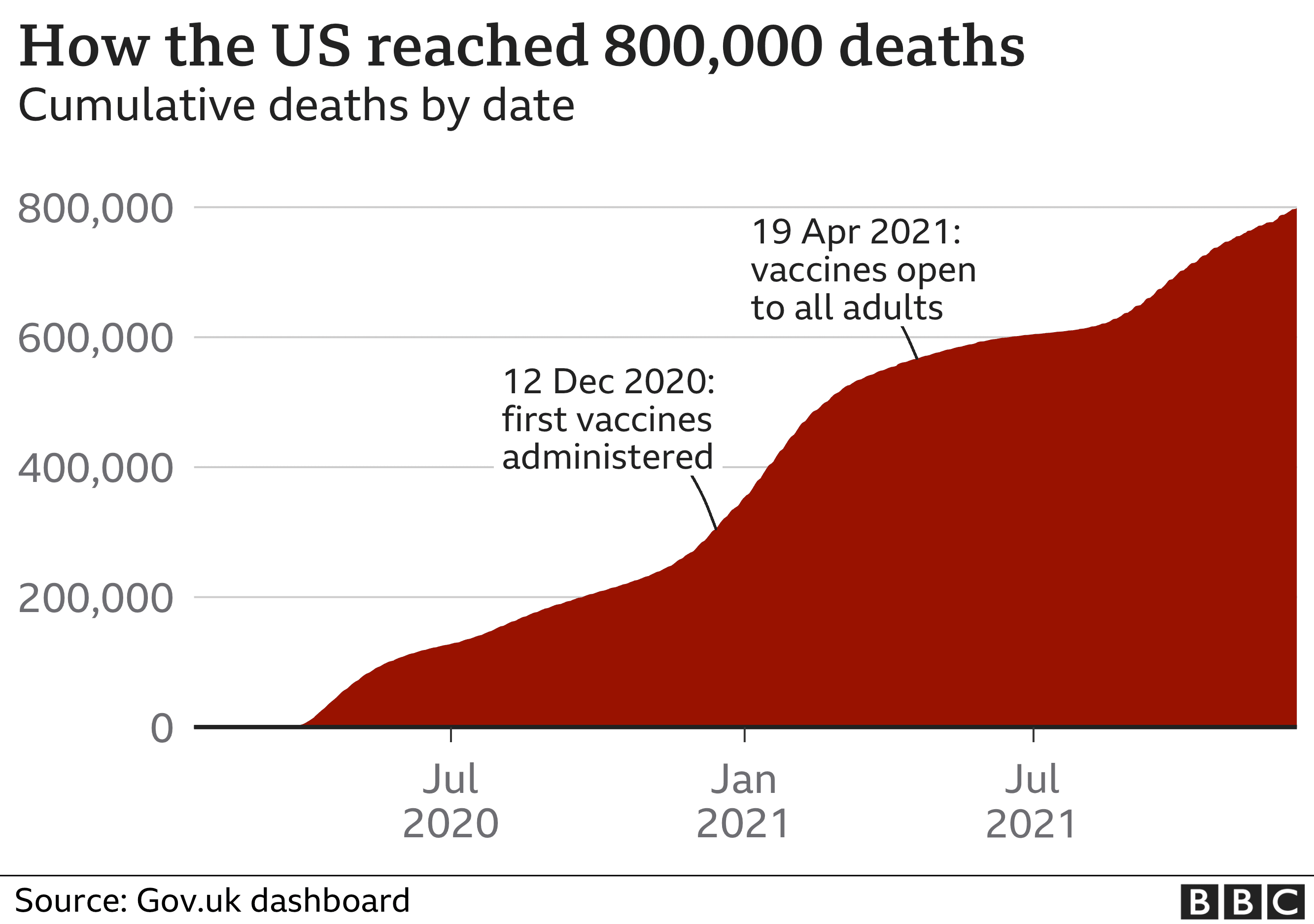

California officially “reopened” that day last year, dropping almost all public health restrictions that had been keeping people mostly at home and preventing the economy from humming back to life. Coronavirus cases were at their lowest levels since the pandemic’s earliest weeks. Hospitalizations and deaths due to COVID had plummeted. Nearly half of all Californians were considered “fully” vaccinated — a remarkable achievement just six months after the vaccines had been authorized.

“This is not mission accomplished,” said Gov. Gavin Newsom on the eve of reopening. But the message was clear in the Bay Area and across the state: The pandemic wasn’t quite over, but with vaccines widely available California was on a path back to normal. The end was in sight.

Reality has played out quite differently. COVID has proved an especially stubborn opponent, rivaling the most infectious pathogens on the planet. But it’s also become a more familiar foe, and one that most Californians are reluctantly learning how to live with.

“June 15 was such a hopeful moment,” said Dr. Susan Philip, the San Francisco health officer. “And then we got delta, and we got omicron,” variants that cast long shadows over the sunny optimism of reopening.

“It’s really important for us to have humility and try to celebrate what all we’ve accomplished,” Philip said. “But it is hard to have a mindset that is able to do that. It’s annoying and difficult right now, and it would be great if we could put it all behind us, but I know that’s not a possibility for the time being.”

The year since California reopened has been about as dynamic and at times disheartening as most any other period of the pandemic. In the past 12 months Californians have endured three more surges and a virus that has become more contagious than anyone ever imagined.

Meanwhile, vaccine efficacy has become more nuanced, especially against a backdrop of rapidly mutating variants of the coronavirus. For a few months after the vaccines were authorized, everyone had reason to hope they would stop or significantly curb the spread of disease. There was still talk of reaching herd immunity, of vaccinating enough people to essentially quash the virus if not out of existence, then to such low levels that it could be ignored by most everyone.

Instead, though the vaccines have held up miraculously well against preventing severe illness and death, they’ve done very little to prevent cases from surging at relentless intervals.

“We’ve learned and reinforced that the vaccines are definitely doing the job of preventing serious illness. But we did not anticipate the immune evasion to happen so quickly with regards to infections,” said Dr. Erica Pan, state epidemiologist with the California Department of Public Health.

California is undoubtedly in a much better place now than it was a year ago, and certainly better off than it was at the start of the pandemic in early 2020. That’s important to remember, health experts say, even in the thick of yet another surge fueled by multiple highly infectious variants.

More people are getting infected than ever, even with now roughly three-quarters of the state’s population vaccinated — but hospitalizations have remained comparably low, and health-care systems are no longer under grave threat of being overwhelmed by COVID patients. COVID deaths, too, have stayed relatively low over most of the past year.

Meanwhile, California has avoided the shutdowns and most other restrictions that defined the first year and a half of the pandemic. Masks have come off and back on, but schools, gyms, restaurants and office spaces mostly have kept their doors open.

“The situation right now is a lot better than it was — like, a lot a lot,” said Dr. Maya Petersen, a UC Berkeley epidemiologist who has done COVID modeling for California during the pandemic. “We’re reframing what the light at the end of the tunnel looks like.”

Petersen recalled that as the state approached June 15 last year, she already was concerned about the delta variant, which was causing a fresh surge in cases in the United Kingdom and was becoming dominant in parts of the United States. Then, she was as frustrated as anyone when it triggered a swell of cases in California just two weeks after reopening.

“July 4 weekend — it was definitely very clear we were in a substantial surge,” she said. “I was like, ‘There goes another holiday.’”

The delta surge was the first discouraging sign that post-vaccine life with COVID wasn’t going to be a return to normal, though at the time many health experts noted that the vast majority of cases, hospitalizations and deaths were occurring in the unvaccinated. They began speaking of “two pandemics,” among those who had gotten their shots and those who had not.

While unvaccinated people remain at much higher risk of severe illness and death than the vaccinated do, the distinction is somewhat less important now. Over the past year scientists have come to understand that immunity wanes and booster shots are critical, especially for protecting older adults and others who are vulnerable to serious illness.

And variants have arrived that evade immunity — both from vaccination and earlier infection. So-called breakthrough infections among the vaccinated are common. So are reinfections.

The omicron wave, which exploded in December and January, brought immunity evasion into especially sharp focus. It was further reinforced by this spring wave of subvariants, which has kept cases astonishingly high even in highly vaccinated places like the Bay Area.

“Things have gotten better over the last year, but we’re still very much in the thick of this,” said Dr. Warner Greene, a senior investigator at the Gladstone Institutes in San Francisco. “Now we’re getting variant upon variant. And if you had an omicron infection, you could get infected again two or three months later by one of these subvariants. The virus is spreading highly, highly effectively.”

Over the past year, the pandemic response has shifted from one of public health mandates to personal responsibility, with an expectation that individuals now have the information and tools to protect themselves based on their own level of risk — and risk tolerance.

That the state has remained open without experiencing the brutal disease and death of the pre-vaccine surges is reason enough to remain hopeful that people can co-exist with the virus, health experts say. But the past year also should provide a hard lesson in the challenges and uncertainty that lie ahead.

“It does feel a little relentless,” said Pan, the state epidemiologist. “I do think over time we’ll get enough immunity, between infections and the vaccines, that it will evolve into something more like the flu and have less impact. But the one thing I’ve learned about trying to predict this virus is it’s unpredictable. It’s quite wily and quite smart.”

Dr. Robert Wachter, chair of the department of medicine at UCSF, has been using social media to help guide people through the pandemic since the earliest weeks. Two days before last year’s reopening, he posted a long thread about his hopes and reservations, which largely focused on his concern for those who had not yet been vaccinated.

A year later, he was writing about his own brush with COVID, in the form of his vaccinated wife’s illness and her subsequent frustration with lingering fatigue and other symptoms.

“I think last year was the only time we allowed ourselves to hope that you could see the end,” Wachter said in an interview. “There was a pretty clear path to: ‘OK, this may never go away completely, but it’s not going to be a big deal, and we can have a regular life, and all that seemed great.’”

But after the past year, “the question is if we are incapable of ever feeling that again,” he said. “You’re always waiting for the next curveball. It makes you feel like any calm period is simply a calm before another storm.”

Erin Allday is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: eallday@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @erinallday