Why is mainland China sticking with “zero-COVID” policy?

Mainland China’s zero-Covid policy is increasingly unsuitable to

contain the much more infectious new coronavirus disease 2019

(COVID-19) variants, yet is likely to remain unchanged this

year.

The policy has exacted heavy tolls on the economy, as containing

outbreaks of the new variants requires extreme restrictions,

including citywide lockdowns. Zero-covid policy lockdowns in the

spring of 2022 caused disruptions to the Chinese economy not seen

since the severe economic contraction in the first quarter of 2020

owing to the initial Covid outbreak in Wuhan.

Hastily relinquished pandemic curbs could lead to large-scale

infections and death surges given the under-resourced medical

system and the large, insufficiently protected elderly population.

That would undermine Chinese Communist Party (CPC) leader Xi

Jinping’s repeated emphasis that “people and lives should come

first.”

Stringent lockdown measures could continue to be the “tool of

last resort” for a dynamically COVID-19-free environment throughout

2022. Near-term dependence on the “test and lockdown” approach

would at least help authorities to mitigate risks of a healthcare

crisis beyond what they are able to control.

Healthcare resource concerns

The strict pandemic responses – also supported by unparalleled

public obedience – have helped keep the domestic COVID-19 infection

count at extremely low levels and reduced disruptions to healthcare

service provisions unrelated to the pandemic. An abrupt relaxation

of the current policy would risk breaking the balance between

COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 healthcare needs and overstretching the

underdeveloped healthcare system.

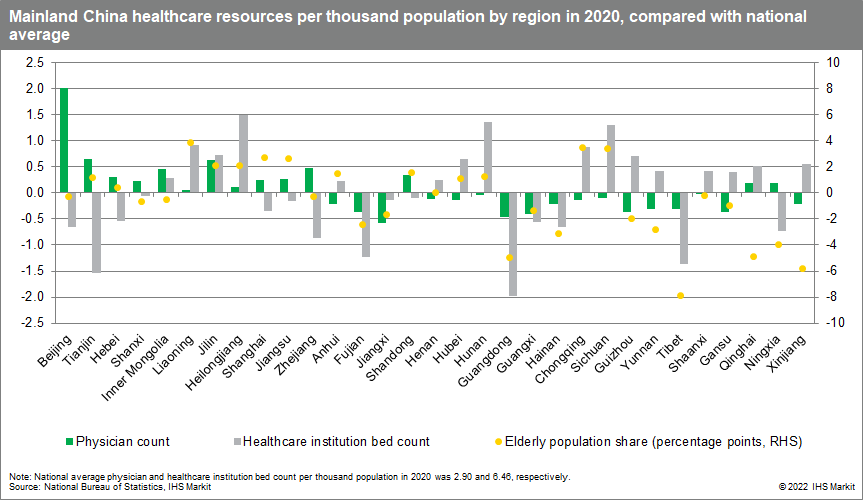

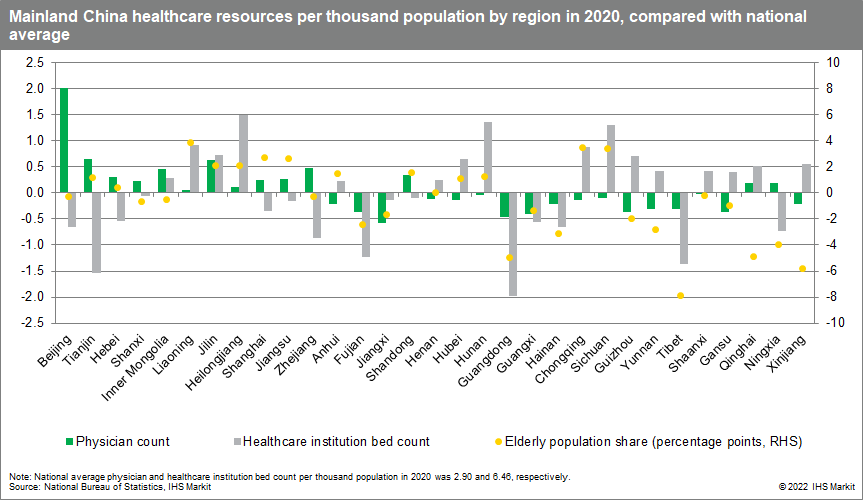

By the end of 2020, mainland China’s number of practicing

physicians reached 2.9 per thousand people compared with 2.6 in the

United States, and 4.4 for the OECD country average. The shortage

of nurses appeared more concerning, as China’s number of nurses per

thousand population was reported at 3.34 – far below the US level

of 12.0 and the OECD country average of 8.8.

China appeared better positioned in terms of medical

infrastructure, with 6.46 beds at healthcare institutions per

thousand people – higher than the level of 2.8 beds in the US, and

the OECD country average of 4.4 beds.

The healthcare systems across the regions have a “physician-hospital bed mismatch” issue – regions with a higher

physician count per thousand people may have insufficient hospital

beds, and vice versa.

More developed areas like the northern coastal region (Beijing,

Tianjin, and Hebei) and the eastern coastal region (Shanghai,

Jiangsu, and Zhejiang) have an above-national-average number of

physicians per thousand people, yet their hospital density is

falling behind.

Less developed regions like the southwest (Sichuan, Chongqing,

Guizhou, Yunnan, and Guangxi) and Midstream Yangtze River (Hunan,

Hubei, Anhui, and Jiangxi) on the contrary have more hospital beds

per thousand people than the national average but fewer

physicians.

Uneven regional distribution of people 65 and older is another

concern. The three northeastern provinces (Liaoning, Jilin, and

Heilongjiang) have both above-national-average numbers of

physicians and hospital beds per thousand people. They also have an

older population – the share of those aged 65 and above among the

local population is 2.9 percentage points higher than the national

average. This is likely to cause relatively greater stress on

healthcare resources amid any significant COVID-19 resurgence.

Vaccination factor

Vaccination is particularly crucial for China, because the

country’s extremely low Covid-19 infection rate indicates the

absence of natural immunity.

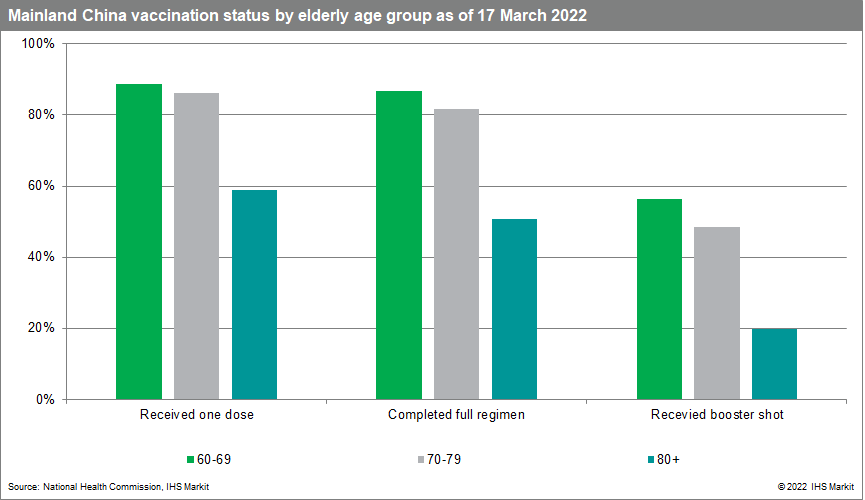

China has achieved a full vaccination rate of nearly 90% and a

booster shot coverage of approximately 55% among the entire

population. Vaccination progress among the elderly lags other age

groups, with hesitancy partially coming from underlying health

conditions, concerns over potential side effects, and the lack of

urgency owing to China’s early containment successes.

The latest release from China’s National Health Commission

suggests that the fully vaccinated share of the population has

reached 82.7% for people aged over 60 years, and only just exceeds

50% for those aged over 80.

At the regional level, reports on full vaccination progress for

the elderly population are limited. In mid-April, at the height of

Shanghai’s latest COVID-19 wave, 62% of the local population aged

above 60 years had reportedly completed a full vaccination regimen.

The share was just 15% for those above 80.

Concerns remain about the unclear efficacy of homegrown vaccines

deployed domestically. In contrast to developed economies that

widely use mRNA vaccines, mainland China has relied heavily on

two-dose inactivated vaccines manufactured by Sinopharm and

Sinovac. In addition, mainland China has approved the use of “mix

and match” booster shots since mid-February 2022 to enhance the

immune response.

A study jointly conducted by the University of Hong Kong and the

Chinese University of Hong Kong found that a third dose of mRNA

vaccine given to those who completed their primary inoculation with

two doses of either inactivated or mRNA vaccines can “provide

protective levels of protective antibody against the Omicron

variant,” while three doses of inactivated vaccines cannot provide “adequate levels of protective antibody.”1 Researchers remarked

that countries primarily using inactivated vaccines should consider

mRNA vaccine boosters to “achieve optimal protection against the

Omicron variant.”

Political considerations

With the 20th CPC Congress scheduled for the end of this year –

during which Xi is expected to secure an unprecedented third term

as leader of the CPC – it is likely that ensuring continuity in

policy, and wide buy-in from local governments on current

governance principles, will be the top priority at all costs.

A recent study by researchers at China’s Fudan University and

the US’s Indiana University validates Beijing’s hesitancy in

relinquishing zero-Covid policy.

The study simulated a scenario in which the Omicron outbreak in

Shanghai in March 2020 was allowed to evolve for six months without

non-pharmaceutical intervention (NPI) measures developed since the

2020 Wuhan outbreak (that is, removing the dynamic zero-COVID

policy).2 In this scenario, the outbreak would result in 112.2

million symptomatic cases, 5.1 million hospital admissions, 2.7

million ICU admissions, and 1.6 million deaths. At peak outbreak,

demand for ICU beds would reach 15.6 times national capacity. A

COVID-19 outbreak that leaves 1.6 million dead and overruns the

healthcare system would pose serious risks to social instability

and is thus politically intolerable.

Theoretically, introducing more effective foreign-made mRNA

vaccines would help to better protect the population against

COVID-19 variants. Chinese authorities have clear political reasons

to prefer domestic vaccines over foreign options. Relying on a

foreign vaccine supplier to establish domestic immunity could

potentially compromise national security. A domestic switch to a

foreign mRNA vaccine would also create negative political optics,

as more than 2 billion doses of homegrown vaccines had been

exported and donated overseas by the end of 2021.

Regardless, the rollout of a more effective vaccine – either

domestically or foreign made – would not fully prevent any fallout

from an exit wave of infections. This suggests that it would have a

rather limited impact on the general principle of dynamic

zero-COVID at the national level, as Xi’s policy for COVID-19

containment includes an extremely low level of infections.

Incentives for stringent pandemic control would be even stronger

at the local level, as any failure of COVID-19 containment would

threaten regional politicians’ careers far more than would an

economic slowdown.

Outlook for future easing

Any meaningful easing of the dynamic zero-COVID approach would

most likely be pushed back until 2023.

When the latest wave is farther in the rare view mirror,

attempts at more sustainable pandemic responses in favor of

commercial interests remain likely. This could be especially true

in areas where significant local lockdown fatigue undermines social

stability and business sentiment. Though actual implementation

would largely hinge on local pandemic situation, mid-tier coastal

cities like Ningbo City of Zhejiang Province, Xiamen City of Fujian

Province, as well as inland cities with stronger economic ties

overseas like Chengdu City of Sichuan Province, could be among the

top candidates to pilot easing, while keeping the risks at a

manageable level.

Possible relaxation measures could include reducing quarantine

requirements and adopting pilot programs in selected cities with

higher vaccination rates and relatively robust medical

capabilities.

The study of uncontrolled Omicron transmission by the

researchers at Fudan University and Indiana University also sheds

light on potential public health policies that could help to ease

the dynamic zero-COVID policy.

The study simulated the impact of Omicron-mitigating measures –

specifically, targeted vaccination of the population aged 60 and

older, and wider utilization of the Chinese government-approved

COVID-19 antiviral medications.

In vaccination simulation for people 60 and older, hospital

admissions were reduced by 33.8% from the baseline scenario to 3.4

million, ICU admissions were reduced by 54.1% from baseline to 1.2

million, and deaths were reduced by 60.8% from baseline to 0.6

million.

Wider use of antivirals resulted in a reduction in

hospitalizations ranging from 36.5% to 81.2% depending on the

medication regimen. A similar impact was seen on ICU admissions and

deaths.

Ideally, progress on the pharmaceutical front – such as more

widely accessible antiviral therapies or more effective vaccines –

would help to reduce the dependence on social and physical

distancing measures.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.