New Omicron-specific vaccines offer similar protection to existing boosters

In the coming days, people in the United States and the United Kingdom will be among the first to receive a new breed of COVID-19 vaccine. The hope was that these updated vaccines — based on Omicron variants — will offer substantially greater protection than older vaccines based on the virus that emerged in 2019. But an analysis1 suggests that updated boosters seem to offer much the same protection as an extra dose of the older vaccines — particularly when it comes to keeping people out of hospital.

“This is not some kind of super-shield against infection compared to what you could have got two weeks ago or a month ago,” says John Moore, a vaccine scientist at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City who was not involved in the modelling study, posted to the medRxiv preprint server on 26 August. US and UK regulators should have taken the potential effectiveness of updated vaccines into account before authorizing them, Moore argues.

On 15 August, the United Kingdom became the first country to approve these ‘bivalent’ vaccines, which are based on the Omicron BA.1 lineage and the original SARS-CoV-2 sequence identified in Wuhan, China, and will soon roll them out. And this week, the US government is expected to greenlight similar bivalent vaccines.

Small efficacy trials

Largescale efficacy trials showed that the first generation of COVID-19 vaccines reduced the risk of disease by more than 90%. But such studies — which involved randomly assigning tens of thousands of people to get a vaccine or placebo and following who got infected — are no longer practical, possible or ethical in 2022.

Updated COVID vaccines have instead been trialled in smaller groups. To gauge effectiveness, developers have typically measured participants’ immune responses, particularly infection-blocking ‘neutralizing’ antibodies, and compared them with those of people who received another dose of the original vaccine.

Most of these trials found that updated vaccines — based not only Omicron, but also older variants including Beta — performed a bit better in this measure than the original vaccines. “This is a clearly superior booster,” Moderna’s president, Stephen Hoge, told investors on 8 June when touting such results from the company’s BA.1-based bivalent vaccine.

To try to make sense of results like Moderna’s, a team led by Deborah Cromer, a mathematical modeller at the University of South Wales (UNSW) in Sydney, Australia, collected all the updated vaccine trial results they could find, as well as studies of fourth doses of the original vaccine.

Both vaccine types sent antibody levels skyrocketing, but the updated versions did so to levels on average 1.5-fold higher than those of older vaccines based on the original SARS-CoV-2 sequence. “We’re not talking about a step change,” Cromer says.

Fewer hospitalizations

Studies suggest that higher levels of neutralizing antibodies equate to better protection against COVID. But it wasn’t clear from the updated vaccine trials how much more effective they might be.

To determine this, Cromer’s team applied a model that she, UNSW immunologist Miles Davenport and their colleagues developed relating efficacy of the original COVID-19 vaccines to antibody levels2. The model found that most of the benefits of updated vaccines come from getting an extra dose of any vaccine.

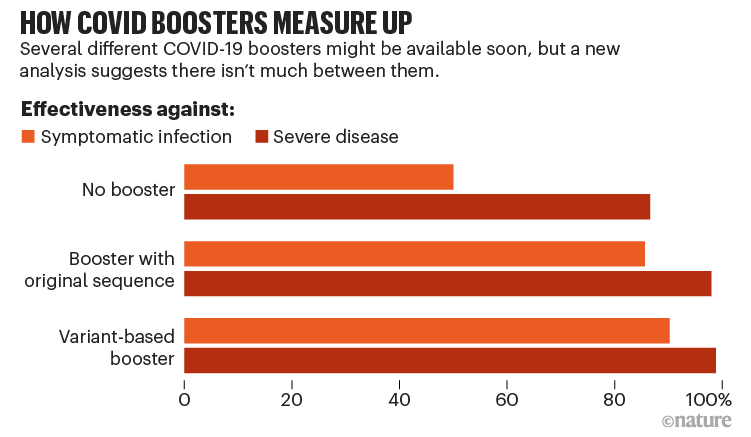

For instance, in a population where half of people are already protected against a symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection through previous vaccines and infection, an updated vaccine booster bumped protection up to 90%, compared with 86% protection provided by an extra dose of the original vaccine. For protection against severe disease, the differences in protection were a few tenths of a percent (see ‘How COVID boosters measure up’).

At a population level, updated vaccines could make sense. Cromer’s team estimated that, for every 1,000 people, a booster campaign based on updated vaccines would result in 8 fewer hospitalizations, on average, than one based on older vaccines. “If that translates to hospital beds saved and severe cases averted, that might be a sufficient level to warrant that the recommendation for a variant modified booster,” she says.

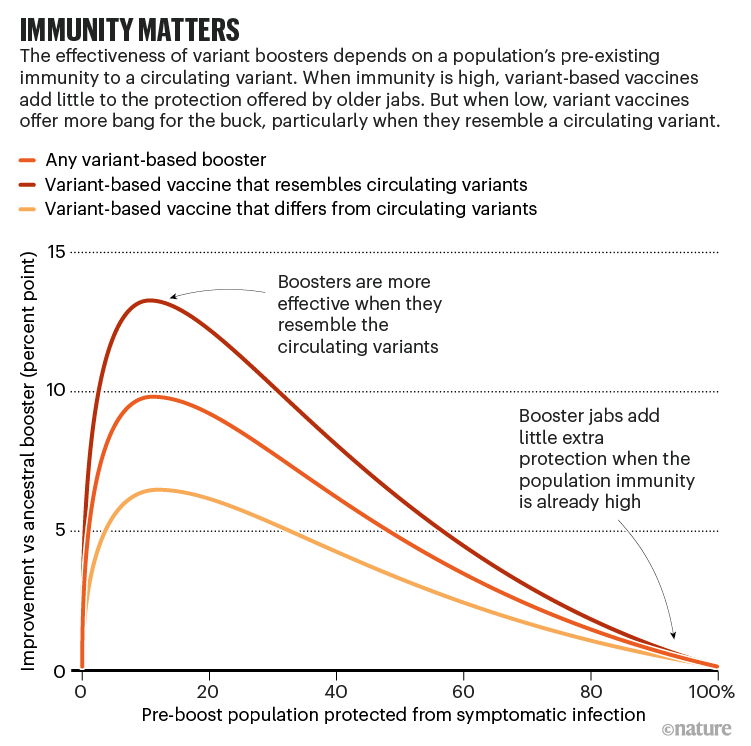

The relative benefits of variant-based boosters could grow stronger, when pre-existing immunity suddenly becomes low because of a new variant (see ‘Immunity matters’). This occurred in December with the emergence of Omicron — and might happen again. In this scenario, an Omicron-based vaccine could provide much better protection than older ancestral vaccines, says Cromer.

Long-term benefit

When the US booster campaign begins, it set to use a different Omicron vaccine from the one approved by the United Kingdom. In June, an advisory committee to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) asked companies to develop bivalent vaccines that were based on the original strain and the BA.4 and BA.5 coronavirus variants — which have identical spike protein sequences — instead of the bivalent BA.1 vaccine that was trialled by Moderna, Pfizer-BioNTech and others. The hope was that, by better matching circulating strains, the vaccines would prove more effective.

But Cromer’s analysis suggests the differences might be paltry. Even updated vaccines based on the Beta and Delta variants should protect against BA.4 and BA.5 infections nearly as well as vaccines based on those variants. Similarly, bivalent vaccines that included the original vaccine looked no more effective than vaccines based solely on a newer variant.

For these reasons, the FDA’s decision to spurn a BA.1-based booster probably wasn’t worth it, says Cromer, particularly as SARS-CoV-2 continues to evolve. “It doesn’t seem to suggest that it’s going to give a dramatic improvement in the effectiveness of the booster vaccine to have that slight change.”

Dean Follmann, a statistician at the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Bethesda, Maryland, says even the marginal benefits of a vaccine based on BA.4 and BA.5 might be enough to justify their roll-out. “It’s probably somewhat better. A lot better — probably not.” Moreover, he says the main message of the analysis should be that any COVID-19 booster is a good one.

Other scientists question the decision to pursue variant boosters, when the benefit is so small. Moore worries that people are being misled into thinking updated vaccines are vastly more effective than existing vaccines, and might then expose themselves to greater infection risks.

Paul Offit, a vaccine scientist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania who was one of two members of an FDA advisory committee to vote against updating COVID-19 vaccines, says Cromers’ analysis underscores his scepticism. “If this vaccine is no more effective than the current vaccines, then why distribute it,” he says. “You’re going to have very little impact on the incidence of severe disease.”

In the long run, it probably makes sense to develop variant-based vaccines, says Cromer, but the idea that they need to closely match circulating viral strains is unrealistic — and counterproductive when highly effective vaccines are already available. “The most important vaccine booster is the one that you actually get.”