‘Citizens’ Attitudes Under Covid19′, a cross-country panel survey of public opinion in 11 advanced democracies | Scientific Data – Nature.com

To conclude the presentation of the CAUCP dataset, we present three key dimensions covered by our survey: policy compliance, attitudinal dynamics, and democratic accountability. We describe three key variables to study the possibly large and lasting effects of the Covid-19 crisis on social and political life.

Public health policy compliance

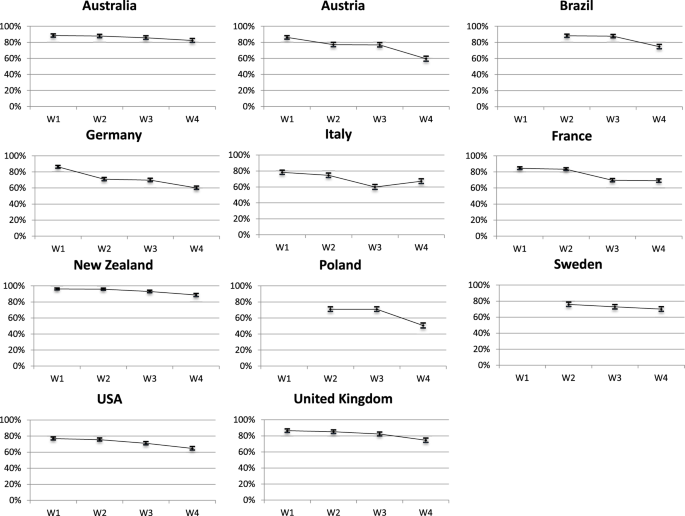

Compliance with Covid-19 related policies is both a salient political debate and constitutes a promising research agenda. Indeed, the preventive and sometimes restrictive policies implemented during the Covid-19 pandemic have been extensively discussed in the public debate. We identify two dimensions of policy compliance: individual behavior (i.e. respecting restrictive regulations) and acceptance/evaluation of Covid-19 related measures (i.e. support for policies restricting individual and civil liberties). Despite sharp political volatility, such as decline (or variations) in trust and negative evaluations of the government, compliance levels to stringent policies remained high21,22 (Newton 2020). However, compliance is mediated by partisanship: support for the parties in government leads to greater compliance23,24. The politics of complying to stringent health policies is certainly influenced by individual and contextual factors. For instance, patterns of compliance to ‘keeping social distance’ diverge across countries, but also evolve over time (Fig. 2). Even in the case of New Zealand which has been less exposed to the coronavirus in terms of fatalities, citizens do react to the Covid-19 related policies and adapt to government recommendations. Indeed, pandemic policies are the most visible policies: virtually all citizens are aware and informed on Covid-19 restrictions. This constitutes a unique research area to evaluate both individual and contextual determinants of policy acceptance.

Compliance: Keeping distance with people outside home. Question wording: “Due to the coronavirus epidemic, in your daily life, would you say that you keep a distance of three feet (1 meter) between yourself and other people outside your home? 0 means “not at all” and 10 means “yes completely”. shows the proportion of respondents who score 10. We consider that the latter respondents are those expressing full compliance to restrictive measures.

Attitudinal dynamics

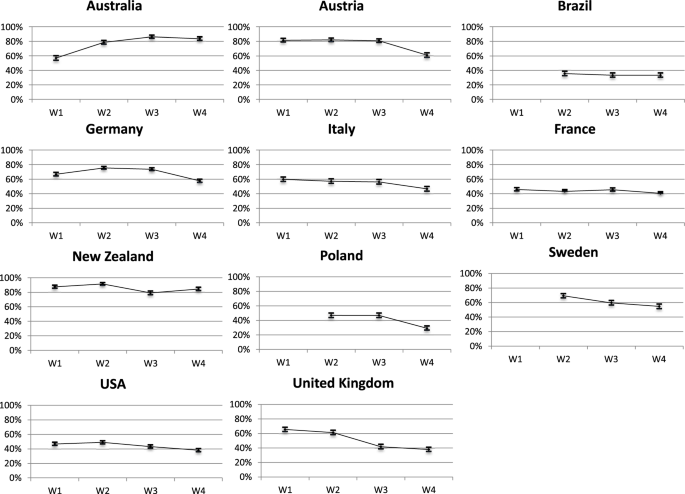

The Covid-19 pandemic had broad consequences for public attitudes. Many pundits and commentators speculate that the Covid-19 may deeply modify political cleavages. The pandemic may also polarize or de-polarize democratic societies. Alternatively, the political impact of the pandemic may be sectoral only, that is, limited to the specific dimensions linked to the crisis. Finally, the Covid-19 pandemic might not be an influential crisis, as long as citizens’ attitudes are concerned, compared to previous major crises, such as geopolitical shocks or economic crises. Still, findings suggest that the pandemic has triggered important attitudinal changes, which however mask individual-level heterogeneity within each country of our sample (for instance Galasso et al. find sizeable gender differences in attitude during the crisis25). What are the factors driving these attitudinal changes? As new issues appeared on the public agendas, there are also opportunities to study the formation of attitudes. Furthermore, many psychological traits, such as personality characteristics, risk perception, emotions are expected to influence political attitudes. Even more, the enormous amount of (mis-) information on the Covid-19 pandemic may have also influenced political attitudes. Indeed, earlier findings have found evidence that different patterns of news consumption affected levels of trust and compliance with Covid-19 related restrictions22. Descriptive findings of the CAUCP survey tend to indicate that the pandemic has not transformed overall political preferences. Indeed, average ideological preferences (Left-Right 11-point scale) are stable over the waves of the panel, and polarization seems unchanged (roughly measured with the standard deviation of the Left-Right scale). Despite a political anchor such as ideology remaining stable throughout the crisis other attitudes tend to fluctuate across time and contexts. For instance, preferences for closing borders have changed during the crisis, although in contrasted directions (Fig. 3).

Preferences for closing the borders to foreigners. Question wording: “Here is a list of measures that have been taken in some countries against the spread of coronavirus (N-Covid19). Do you agree with them? The closing of the borders for foreigners” – 5-point Likert Scale. shows the proportion of respondents who “completely agree” or “tend to agree”.

Even further, the political consequences of the pandemic seem to be mediated by anxiety rather than a cognitive trigger of the political ‘rally’ effect26. The CAUCP offers a promising agenda for research in political psychology with a large battery of questions on emotions and social interactions.

Democratic accountability

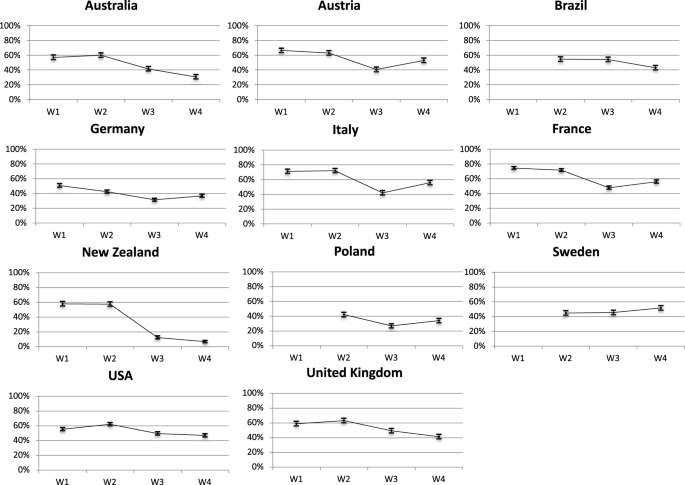

Studying the consequences of the Covid19 pandemic in terms of democratic accountability represents a rich research agenda. Citizens’ responses to the unprecedented pandemic policies, and to the subsequent expected economic crisis, is crucial to understand the functioning of democracies and will most likely be multifaceted (electoral behavior, trust and evaluation of institutions and policies, blame attribution). For instance, initial findings on citizens’ response to the Covid-19 pandemic show a ‘rally around the flag effect’27,28. However, this effect should be qualified since it is neither universal29 nor similarly lasting as the crisis endures30, or rather producing a ‘crisis signal effect that benefits incumbents’31. Research suggests that the pandemic has triggered stronger support or satisfaction with the governments and their policy – largely mediated by levels of trust and partisanship32. The CAUCP data confirms that citizens’ policy response is complex and context dependent. Looking at the satisfaction with the government’s handling of the Covid19 crisis, we observe important time and country variation (Fig. 4). Indeed, in the different countries, the level of satisfaction is extremely high (Australia, New Zealand, Austria), average (France, Italy, USA), or generally low (Brazil, Poland). Additionally, trends of satisfaction are either increasing (Australia), stable (France, New Zealand), or declining (Sweden, United Kingdom). In addition to attitudes toward the government, social science research should further investigate the electoral consequences of the crisis. Indeed, local sanitary contexts and corresponding health policies have affected turnout rates in several European local elections, increasing turnout in some cases33 or depressing it in others34,35. Further, the Covid19 pandemic has influenced voting behavior, generally to the benefit of incumbents and Green parties in local elections36. How consistent are these patterns? Are they dependent on the context of the pandemic and the policy response? Do they hold for national and local elections? Such questions enable to investigate promising research venues on the effects of retrospective vote choice on attitudes, as well as on the consequences of the crisis on prospective vote choice, and actual electoral behavior as three countries held national elections in 2020 (USA, New Zealand, and Poland). Evaluating the significance of individual-level health and economic situations on political behavior and attitudes constitute a promising research lead, as most studies examined these questions at the aggregate level thus far.