Black COVID patients were delayed treatment because of one medical device. Why are doctors still using it?

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, East Bay Dr. Stephanie Brown began noticing a startling trend. Many of her Black patients were getting worse, even while their oxygen measurements said the opposite.

Like her fellow emergency-room physicians, Brown was relying on pulse oximeters, the standard tool for measuring a patient’s blood oxygen level, to assess a critical cut-off point determined by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control. Anything below 95% indicated a severe case of COVID-19 and the need for more intensive treatment, while those at 95% and above typically had milder symptoms.

But again and again, the device failed to capture what Brown was seeing.

“Patients were sicker than what the pulse oximeter was showing,” recalled Brown, who is also the clinical lead at the Sutter Health Institute for Advancing Health Equity. “You could get a 95 or 96% reading on a Black patient, but then look at them and think: They’re breathing so fast and they don’t look good. The numbers weren’t adding up.”

A pulse oximeter on Ronald Young’s finger measures his blood-oxygen level at Roots Community Health Center in Oakland, Calif., on Wednesday, Nov. 30, 2022. The nonprofit says the device may be partially responsible for troubling disparities that have Alameda County’s Black residents dying from COVID at twice the rate of white residents.

Salgu Wissmath / The Chronicle

In September, a study from Sutter Health showed that pulse oximeters can give inaccurate readings for darker-skinned patients. According to the study, those inaccuracies led to nearly five-hour treatment delays for Black COVID-19 patients, and may have contributed to the death disparities plaguing the Black community since the beginning of the pandemic in March 2020.

The problem extends far beyond COVID-19. Pulse oximeters are used for assessing the health of patients dealing with numerous respiratory illnesses, heightening fears as a “tripledemic” of respiratory illnesses circulates this winter.

Oakland’s Roots Community Health Center, one of the organizations behind the study, is now asking pulse oximeter manufacturers and purveyors to either redesign their products or provide warnings on their shortcomings. In letters to 11 companies sent out last month, the organization said that if neither occurs, Roots will bring those corporations to court — and attempt to prohibit sales across California until their requests are met.

“We weren’t going to accept just doing the research and letting it sit on a shelf,” said Dr. Noha Aboelata, the founder of Roots and one of the study’s co-authors. “We want the devices to be fixed, and we are looking to pursue any and all avenues we can to see that happen.”

CEO Dr. Noha Aboelata at Roots Community Health Center in Oakland, Calif., on Wednesday, Nov. 30, 2022. Aboelata co-authored a study that showed a common medical device is giving inaccurate oxygen readings for darker-skinned patients, creating troubling disparities in the treatment of COVID sufferers.

Salgu Wissmath / The Chronicle

The impact of just 1%

Sutter’s study is just the latest of many showing pulse oximeters can overestimate blood oxygen levels for people of color, with reports dating back to 1999. According to Aboelata, that overestimation occurs on a gradient: The darker a person’s skin tone, the more difficult it is for the device’s light to pass through the patient’s tissue, affecting the detection of oxygen in the patient’s blood.

It’s something doctors understood to an extent, as providers routinely remove nail polish from patients before placing a pulse oximeter on their fingertips. But realizing these same issues extend to the color of a patient’s skin? That, Aboelata said, felt like uncovering a scandal.

“It had my mind spinning,” Aboelata said. “Were there times where I could have not done the right thing based on this measurement?”

In December 2020, researchers in Michigan found Black patients were three times more likely than white patients to have low blood oxygen levels that were missed by pulse oximeters. In February 2021, the CDC issued updated guidelines on the use of pulse oximeters, noting the devices could prove inaccurate for people of color. And in September of this year, Sutter analyzed the impact of those discrepancies in Northern California, and suggested they may be one reason why Black patients faced higher death rates than their white counterparts.

Dr. Tolbert Small, right, sees patient Ronald Young, left, at Roots Community Health Center in Oakland, Calif., on Wednesday, Nov. 30, 2022.

Salgu Wissmath / The Chronicle

According to California’s Department of Public Health, the COVID-19 death rate is 20% higher for Black Californians when compared to the rest of the state’s residents. And in Alameda County, where Roots is based, Black residents are dying from COVID-19 at twice the rate of white residents.

By analyzing nearly 44,000 twin measurements — one from a pulse oximeter, and the other from an arterial blood gas test, which draws blood from an artery in the wrist — the Sutter study found pulse oximeters routinely overestimated Black patients’ blood oxygen levels by an average of 1%.

With a clinical cut-off point of 95%, that 1% difference meant patients could be discharged or turned away from the hospital based on a “healthy” pulse oximeter reading, with doctors unaware the device was calibrating incorrectly for people of color.

“If you’re above the threshold for admission, you’re getting sent home — that’s just the bottom line,” said Dr. Kim Rhoads, founder of Umoja Health and the director of community engagement at the UCSF Cancer Center. “If you’re getting sent home, you’re not getting any of the support that would be needed to nurse you through COVID.”

The study also found that because of faulty readings, Black patients faced up to a 4.5-hour delay in receiving supplemental oxygen. Patients were less likely to be admitted to the hospital overall and may have been sent home prematurely if they did get there, the researchers said.

Still, as the pandemic progressed, pulse oximeters remained an essential tool for assessing the severity of a COVID-19 infection. Throughout the country, most hospital workers remained unaware of the design flaw.

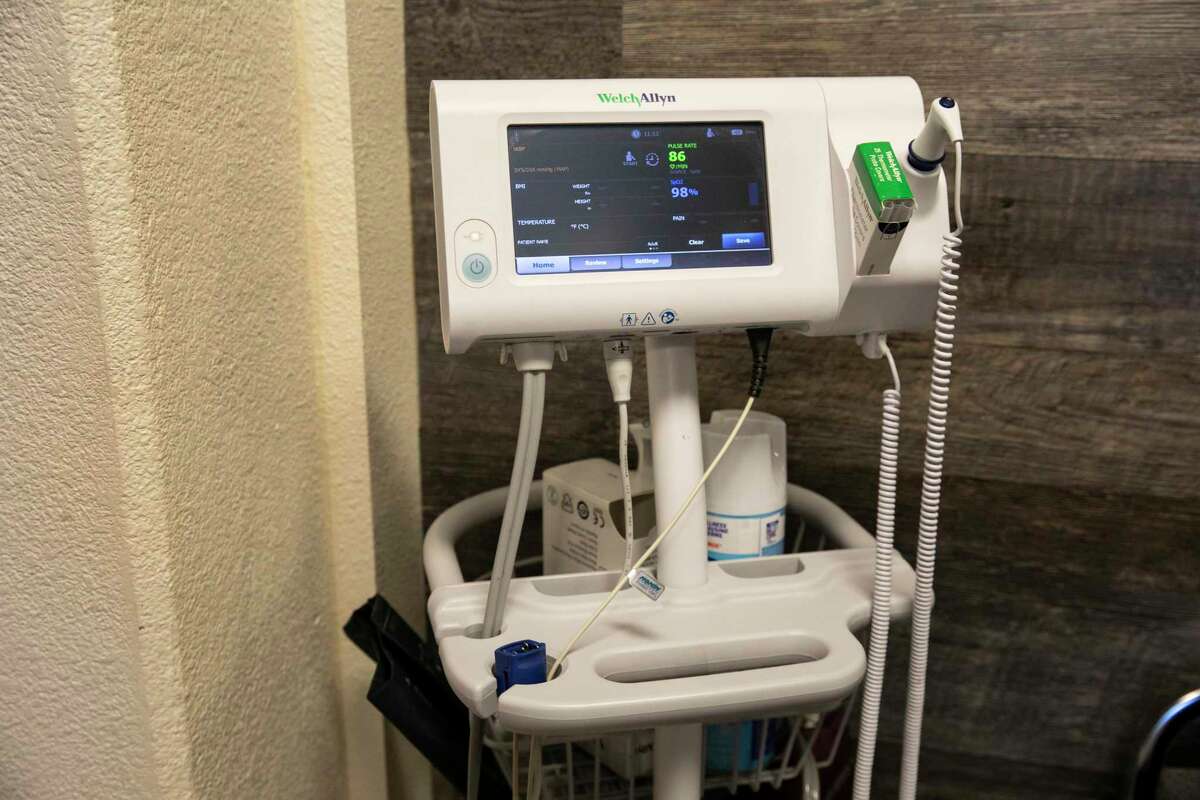

A vital signs stand at Roots Community Health Center in Oakland, Calif., on Wednesday, Nov. 30, 2022. A “tripledemic” of respiratory illnesses this winter has heightened the urgency around the use of pulse oximeters, which research shows have trouble accurately measuring the blood-oxygen levels of darker-skinned patients.

Salgu Wissmath / The Chronicle

Untangling the death disparity among Black Americans

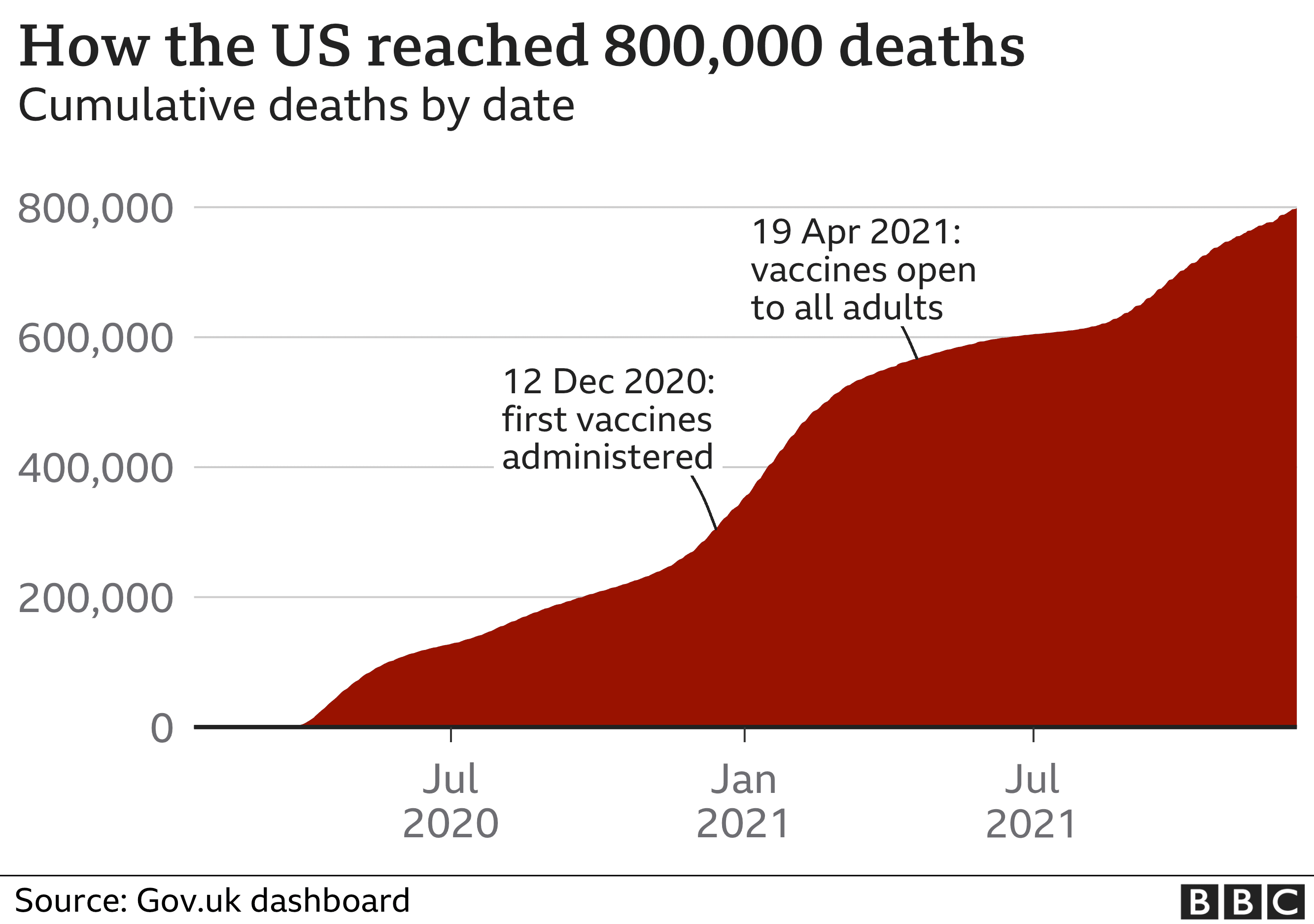

Two-and-a-half years after the onset of the pandemic, Black Americans are still 1.7 times as likely to die from COVID-19 as white Americans, despite vaccination rollouts and increased understanding of the virus, according to the CDC.

The reasons underlying this disparity are complex. Black Americans are, across the country, more likely to hold occupations that increase their exposure to COVID-19. According to Brown, their health is also more likely to be shaped by negative social factors, including their environment and income levels.

But for all three experts, the impact of faulty pulse oximeter readings could not be ignored.

An earlier Sutter study found Black patients were hospitalized at nearly three times the rate of both white and Hispanic patients. Kristen Azar, the scientific medical director at Sutter Health Institute for Advancing Health Equity and co-author of both studies, said delayed care from faulty pulse oximeter readings may have contributed to that.

“Because the pulse ox is the gatekeeping mechanism to determine if you’re going to get admitted (to the hospital) or not, it has huge implications,” said Rhoads, another co-author of the study. “Everything else downstream is either delayed or not delivered if you don’t meet the criteria based on the pulse oximeter.”

For doctors like Aboelata, who were already worried about implicit bias within the healthcare system, the study’s findings were an indictment.

“I think back to when we had all those images, lines of people waiting outside the hospital because there weren’t enough beds,” Aboelata said. “How many times was a person turned away and told they weren’t sick enough based on what looks like a normal pulse oximeter reading?”

Dr. Arghavan Salles, a clinical associate professor at Stanford University, said such issues are a result of the medical system being designed around one type of person: a 70-kilogram white man. Pulse oximetry inaccuracies are one symptom of a larger problem, she said.

Today, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration requires pulse oximeter trials to have at least 15% of their subjects be darker skinned. It’s a number which, for some researchers, feels far below what is needed to manufacture a device calibrated for all skin tones.

In a letter responding to Roots’ threat to sue, Masimo, a California-based manufacturer of pulse oximeters and other medical devices, stated its trials have “roughly equal” numbers of darker- and lighter-skinned subjects. Earlier this month, the company published a review of its data, which showed no significant difference in accuracy for subjects of different skin tones. It also noted not all pulse oximeters have the same reliability.

Though Brown and Azar welcomed the potential of Masimo’s data, they pointed out that the Sutter study did not focus on just one brand of pulse oximeter and that they are one of a flood of studies analyzing pulse oximetry reliability since the onset of COVID-19.

“This is helpful information, but it still brings up further questions,” Azar said. “As we make policies going forward, are we doing so based on something that could potentially be biased? We need all companies to be involved.”

Looking forward

Today, the only alternative to a pulse oximeter is a blood arterial test, which extracts blood straight from a patient’s artery. It’s a painful test that takes time and skill to perform. Because of that, Aboelata feels that to truly address the pulse oximeter disparity, manufacturers will need to start from scratch.

In the meantime, Roots is pushing for companies to label the potential inaccuracies of pulse oximeters — at minimum — to hold the $2.3 billion industry accountable.

The Oakland-based organization isn’t the only one. Last month, experts from across the country met with the FDA to highlight concerns about pulse oximeters, push for additional studies and encourage labeling of devices for both hospital and over-the-counter use.

According to Azar, doing so could help not just COVID-19 patients, but also those fighting other illnesses. Black patients suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, for example, may have been denied supplemental oxygen treatment or insurance coverage due to that one percentage point miscalculation.

Still, reliance on pulse oximeters is growing. According to San Francisco-based market analytics firm Grand View Research, the industry’s value is expected to rise to $2.8 billion by the end of the decade, driven by the onset of COVID-19 and increasing rates of other respiratory illnesses.

Bay Area hospitals are already feeling the strain of those spikes, including rising flu cases and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in children. In late October, the California Department of Public Health reported rates of RSV not typically seen until late November. Halfway through that month, the Santa Clara County health department said emergency department visits for flu-like illness about tripled the rate of the same period during the 2019-2020 flu season.

Roots received responses from six out of 11 companies and manufacturers by the Nov. 16 deadline. Now, the organization is assessing each response to determine its next steps.

In the meantime, Aboelata is telling patients to bring the Sutter study with them to the hospital. If their physician is not aware of the potential for pulse oximetry inaccuracies, they need to be ready to advocate for themselves, she said, and to demand an arterial blood gas test if there is any doubt in their blood oxygen levels.

“This device is clearly aiding — and making — life or death decisions,” Aboelata said. “So it’s imperative we get it right.”

Elissa Miolene is a freelance journalist based in San Francisco. Twitter: @elissamio