Arizona secretary of state primary election results: August 2022

Arizona secretary of state primary election results: August 2022 The Arizona Republic

The last election set the tone for this year’s races for Arizona secretary of state, bringing out election deniers, election skeptics and election defenders.

Which two candidates — and which points of view — will advance to the November election will be known when the results of Tuesday’s primary are in. The first results are expected about an hour after polls close at 7 p.m., but a close race could delay the declaration of a winner for days.

On the Republican side, four candidates are competing for the state’s top elections post: state lawmakers Shawnna Bolick, Mark Finchem and Michelle Ugenti-Rita, along with businessman Beau Lane. The race was comparatively low-key given the increased attention to voting in the still-disputed wake of the 2020 presidential election.

The two-way race between Democrats Reginald Bolding and Adrian Fontes heated up in the closing weeks, amid revelations of missing tax returns, the role of “dark money” groups and unpaid tax bills.

All of the candidates talk about increasing confidence in elections. But they differ significantly in how they would do that.

The Republican candidates

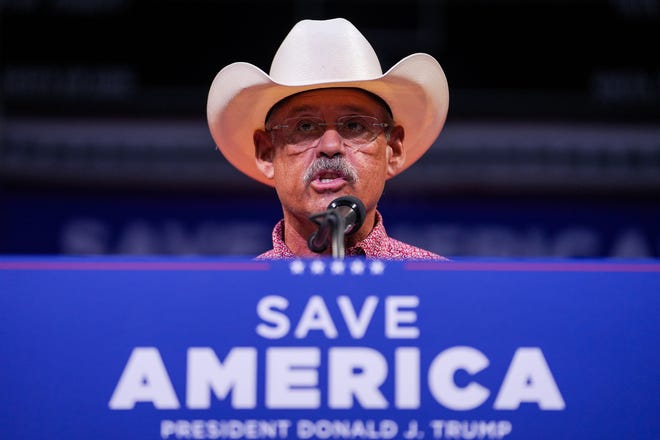

Among Republican candidates, Finchem, a four-term state representative from Oro Valley, has staked out the most extreme view, insisting despite evidence to the contrary that Donald Trump was cheated out of the presidency in the 2020 election.

His unwavering support for the “Stop the Steal” movement earned him Trump’s first endorsement in Arizona. He helped organize two public meetings in the wake of the 2020 election to cast doubt on election procedures and turned what he said was evidence of election fraud over to the state Attorney General’s Office. The office has taken no action on his complaints.

Finchem, who was near the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, portrayed the insurrection as a protest from people who feel they have been ignored. He has the support of election deniers and white nationalists, including Gab founder Andrew Torba and Seth Keshel, a former Army intelligence officer who promotes election-fraud theories.

Finchem wants to abolish early voting, banish electronic machines, and see the creation of specially formatted ballot paper to guard against fraud. He wants a return to precinct-based voting (as opposed to voting centers) and to a hand count of ballots. Last month, he said if he gets a whiff of any election impropriety, he would challenge the results.

Bolick, a two-term representative from Phoenix, has campaigned to tighten election procedures, but her solutions are not as extreme as Finchem’s. She has called for a ban on ballot drop boxes, better coordination and oversight of the 15 county recorders whose offices actually run the election, and creation of a citizen audit review board.

She continues to have doubts about the 2020 election, saying it was “rigged” because elections offices used private grant money that was offered to offset the increased cost of running an election during a pandemic. She charged elections officials “colluded” with the courts, but has not offered any specifics.

She sponsored a bill that would have allowed state lawmakers to disregard the slate of electors chosen by voters in a presidential election and to replace them with electors of their choosing.

Ugenti-Rita, a legislative veteran from Scottsdale, has stood out from her opponents because she has successfully run election-related legislation that was signed into law. She championed a bill to drop infrequent voters from a list that automatically sends them a ballot, ending the state’s Permanent Early Voting List and replacing with the Active Early Voting List.

She gets credit for legislation that ended the practice of mass collection of ballots, or so-called “ballot harvesting.”

Ugenti-Rita’s legislation has taken a more deliberate, cautious approach to changing election procedures, rather than the sweeping changes some of her opponents have pushed.

She accepts the 2020 election results and has ridiculed her opponents who would opt to decertify election results, or refuse to sign off on the will of the voters.

Lane is the outsider of the GOP pack, although he has drawn support and financial support from many of the state’s business and political power brokers.

The executive chairman of Lane|Terralever, an advertising firm that has its roots in a company his father founded 60 years ago, Lane is running as the antidote to the “dysfunction” that he sees among politicians when it comes to elections.

He has advocated a steady-as-she-goes approach to the office and is quick to say that Joe Biden won the 2020 election. His platform drew a key endorsement from Republican Gov. Doug Ducey, who called him a trustworthy candidate who’s not seeking to play politics with the office.

Two Democrats vie for nomination

Bolding and Fontes are in a dogfight for the Democratic nomination. Both men have similar stances on election matters, agreeing on the need to protect election processes and expand voter engagement, while rejecting the radical overhaul promoted by Finchem, whom they view as the likely GOP nominee.

But in the closing weeks of the campaign, the two have diverged along more personal lines.

Bolding, the minority leader in the Arizona House, has come under scrutiny for the role one of his voter-oriented nonprofits has played in his campaign. He has benefited from nearly $1 million in spending from Our Voice Our Vote, a so-called “dark money” organization that doesn’t have to disclose its donors and that has paid Bolding’s salary as co-executive director, along with his wife.

Bolding has accepted the support of the group, maintaining he has a “firewall” agreement that cuts him out of any political decisions the group makes.

Fontes, the former Maricopa County recorder, has criticized the cozy appearance of the arrangement, which has prompted complaints to state and federal officials for improper campaign coordination.

Fontes was targeted by pro-Bolding groups for missteps during his tenure as county recorder, portraying him as too rash and impulsive. It took a lawsuit to halt his attempt to mail ballots to every voter in the 2020 Democratic presidential preference election, a stance he said he took as a safeguard during the COVID-19 pandemic. Problems with the 2018 general election led to long lines at the polls.

However, the 2020 election that Fontes oversaw went off with few problems. Its results were verified by numerous audits, including the highly publicized ballot review ordered by state Senate Republicans, and has withstood numerous legal challenges.

Late in the campaign, Fontes paid off a 9-year-old property tax bill for a vacant lot he owns in Santa Cruz County. He said he never received billing statements, which county officials confirmed were sent to a Lake Havasu City address instead of Fontes’ Phoenix residence. He paid the $3,700 balance when he learned of the missing payments.

Reach the reporter at maryjo.pitzl@arizonarepublic.com and follow her on Twitter @maryjpitzl.

Support local journalism. Subscribe to azcentral.com today.