Accuracy prompts are a replicable and generalizable approach for reducing the spread of misinformation – Nature.com

We begin by examining the overall effect of the various accuracy prompts on sharing intentions across all experiments. Recall that in each study, participants were randomized to receive or not receive an accuracy prompt prior to indicating their sharing intentions for a series of true and false headlines. For analyses, sharing intentions (which were typically collected using a 6 point Likert scale) are scaled such that 0 corresponds to the minimum scale value and 1 corresponds to the maximum scale value. Thus, it is the [0,1] interval that is relevant for interpreting the magnitude of regression coefficients (e.g., if sharing intentions were binary, coefficients would be in units of percentage points). We also provide percentage changes relative to control to help contextualize the effect sizes. All statistical tests are two-tailed.

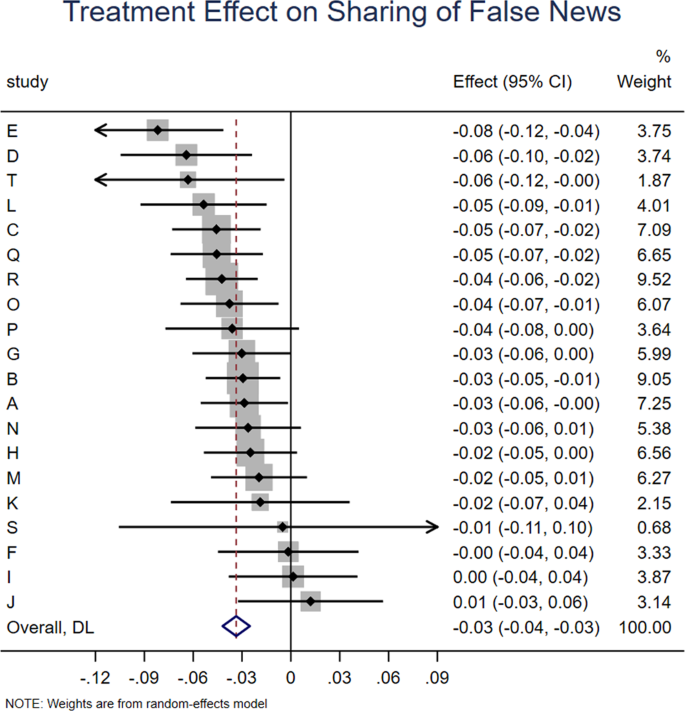

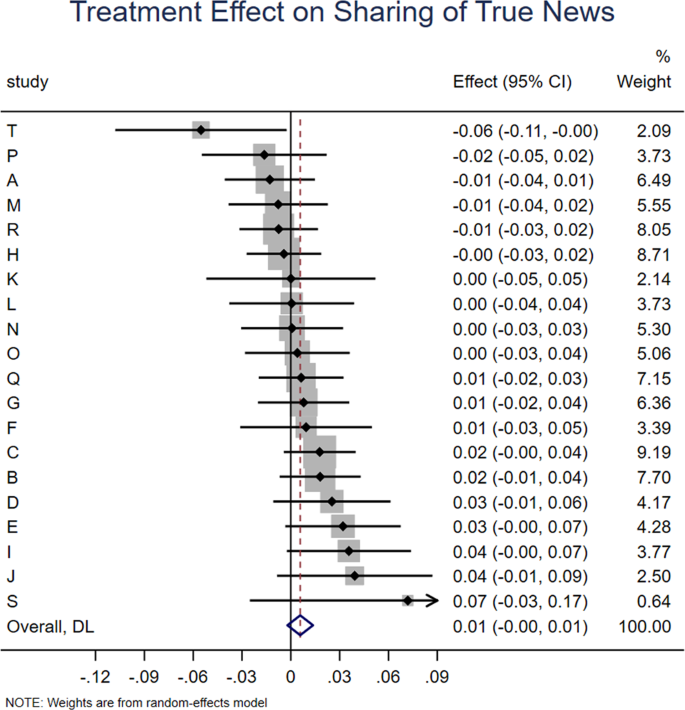

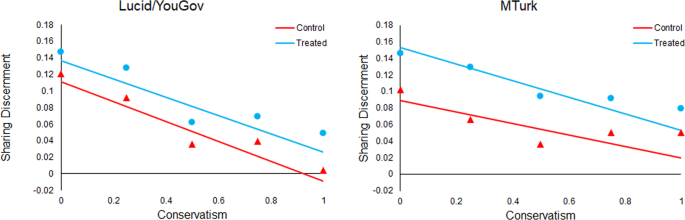

We find that accuracy prompts significantly increase sharing discernment (interaction between headline veracity and treatment dummies: b = 0.038, z = 7.102, p < 0.001; Fig. 1), which translates into a 71.7% increase over the meta-analytic estimate of baseline sharing discernment in the control condition (headline veracity dummy: b = 0.053, z = 6.636, p < 0.001). This increase in discernment was driven by accuracy prompts significantly decreasing sharing intentions for false news (treatment dummy: b = −0.034, z = 7.851, p < 0.001; Fig. 2), which translates into a 10% decrease relative to the meta-analytic estimate of baseline sharing intentions for false news in the control condition (intercept: b = 0.341, z = 15.695, p < 0.001). Conversely, there was no significant effect on sharing intentions for true news (treatment dummy from model with true as holdout for headline veracity: b = 0.006, z = 1.44, p = 0.150; Fig. 3). Average baseline sharing intentions was 0.341 for false headlines and 0.396 for true headlines; average sharing intentions following an accuracy prompt was 0.309 for false headlines and 0.404 for true headlines; for average sharing intentions by headline veracity and condition in each experiment, see Supplementary Information, SI, Section 1.

Meta-analytic estimate (via random effects meta-analysis) of the effect of accuracy prompts on sharing discernment across the 20 experiments analyzed in this paper. The coefficient on the interaction between condition and headline veracity and 95% confidence interval are shown for each study, and the meta-analytic estimate is shown with the red dotted line and blue diamond (positive values indicate that the treatment increased sharing discernment). We find significant heterogeneity in effect size across studies, Cochran’s Q test, Q(19) = 88.53, p < 0.001, I2 = 78.5% (k = 20 independent studies).

Meta-analytic estimate (via random effects meta-analysis) of the effect of accuracy prompts on sharing of false news across the 20 experiments analyzed in this paper. The coefficient on the condition dummy (which captures the effect of the treatment on sharing of false headlines) and 95% confidence interval are shown for each study, and the meta-analytic estimate is shown with the red dotted line and blue diamond. We find no significant heterogeneity in effect size across studies, Cochran’s Q test, Q(19) = 23.33, p = 0.223, I2 = 18.5% (k = 20 independent studies).

Meta-analytic estimate (via random effects meta-analysis) of the effect of accuracy prompts on sharing of true news across the 20 experiments analyzed in this paper. The coefficient on the condition dummy when analyzing true headlines and 95% confidence interval are shown for each study, and the meta-analytic estimate is shown with the red dotted line and blue diamond. We find no significant heterogeneity in effect size across studies, Cochran’s Q test, Q(19) = 22.42, p = 0.264, I2 = 15.3% (k = 20 independent studies).

We find similar results when only considering the Evaluation treatment – where participants were asked to evaluate the accuracy of a single neutral headline at the outset of the study – which was the most-tested accuracy prompt (k = 14 experiments). The Evaluation treatment significantly increased sharing discernment (interaction between headline veracity and treatment dummies: b = 0.034, z = 7.823, p < 0.001), which translates into a 59.6% increase over baseline sharing discernment in the control condition (headline veracity dummy: b = 0.057, z = 7.2, p < 0.001). This increase in discernment was again largely driven by the Evaluation treatment significantly decreasing sharing intentions for false news (treatment dummy: b = −0.027, z = −5.548, p < 0.001), which translates into an 8.2% decrease relative to baseline sharing intentions for false news in the control condition (intercept: b = 0.330, z = 14.1, p < 0.001); the effect on sharing intentions for true news was again non-significant, b = 0.009, z = 1.89, p = 0.059.

To gain some insight into whether there are additive effects of exposure to multiple accuracy prompts, we compare the results for the Evaluation treatment described above to the various conditions in which the Evaluation treatment was combined with at least one additional treatment (either repeated Evaluations, indicated by “10x” in Table 2, or alternative treatments, indicated by “+” in Table 2). The combination of Evaluation and additional treatments significantly increased sharing discernment (interaction between headline veracity and treatment dummies: b = 0.054, z = 2.765, p = 0.006, which translates into a 100.8% increase over baseline sharing discernment in the control condition of those experiments (headline veracity dummy: b = 0.050, z = 2.92, p = 0.003). This increase in discernment was again largely driven by a significant decrease in sharing intentions for false news, b = −0.048, z = −2.990, p = 0.003, which translates into a 16.5% decrease relative to baseline sharing intentions for false news in the control condition of those experiments (intercept: b = 0.291, z = 8.7, p < 0.001); the effect on sharing intentions for true news was again non-significant, b = 0.008, z = 0.775, p = 0.438. Although not a perfectly controlled comparison, the observation that the combined treatments were roughly twice as effective as Evaluation alone suggests that there are substantial gains from stacking accuracy prompt interventions.

To test if the effect is unique to the Evaluation treatment, we examine the results when only including treatments that do not include any Evaluation elements. The non-evaluation treatments significantly increased sharing discernment (interaction between headline veracity and treatment dummies: b = 0.039, z = 4.974, p < 0.001), which translates into a 70.9% increase over baseline sharing discernment in the control condition of those experiments (headline veracity dummy: b = 0.055, z = 7.1, p < 0.001). This increase in discernment was again largely driven by a significant decrease in sharing intentions for false news, b = −0.039, z = −5.161, p < 0.001, which translates into a 11.0% decrease relative to baseline sharing intentions for false news in the control condition of those experiments (intercept: b = 0.356, z = 16.6, p < 0.001); the effect on sharing intentions for true news was yet again non-significant, b = 0.002, z = 0.338, p = 0.735. Thus, the positive effect on sharing discernment is not unique to the Evaluation intervention.

Study-level differences

Next, we ask how the size of the treatment effect on sharing discernment varies based on study-level differences. Specifically, we consider the subject pool (convenience samples from MTurk versus more representative samples from Lucid/YouGov), headline topic (politics versus COVID-19), and baseline sharing discernment in the control condition (indicating how problematic, from a news sharing quality perspective, the particular set of headlines is).

These quantities are meaningfully correlated across studies (e.g., MTurk studies were more likely to be about politics, r = 0.63; and baseline sharing discernment was lower for political headlines, r = −0.25). Therefore, we jointly estimate the relationship between the treatment effect on discernment and all three study-level variables at the same time, using meta-regression. Doing so reveals that the treatment effect is significantly larger on MTurk compared to the more representative samples, b = 0.033, t = 2.35, p = 0.032; and is significantly smaller for headline sets where discernment is better at baseline, b = −0.468, t = −2.42, p = 0.028. (Importantly, we continue to find a significant positive effect when considering only experiments run on Lucid or YouGov, b = 0.030, z = 7.102, p < 0.001.) There were, however, no significant differences in the effect for political relative to COVID-19 headlines, b = −0.017, t = −1.21, p = 0.244.

Item-level differences

Next, we examine how the effect of the accuracy prompts on sharing varies across items, in a more fine-grained way than simply comparing headlines that are objectively true versus false. Based on the proposed mechanism of shifting attention to accuracy, we would expect the size of the treatment effect to vary based on the perceived accuracy of the headline (since participants do not have direct access to objective accuracy). That is, to the extent that the treatment preferentially reduces sharing intentions for false headlines, the treatment effect should be more negative for headlines that seem more implausible.

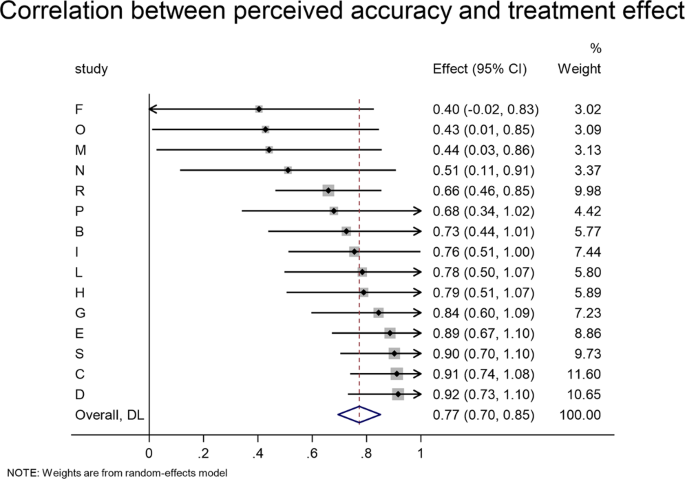

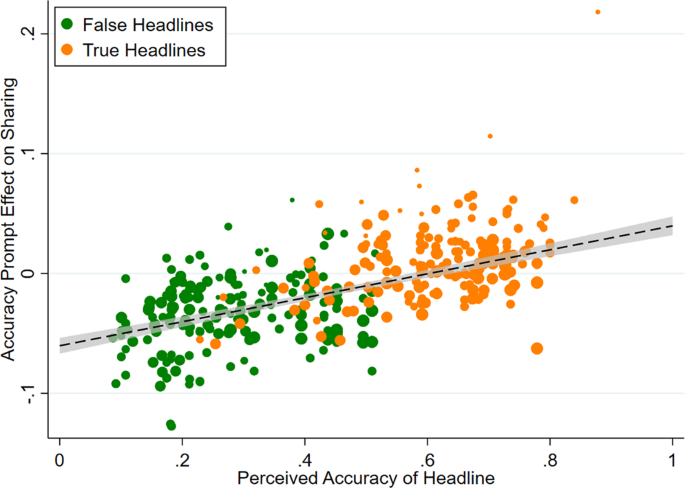

In these experiments, however, participants do not rate the accuracy of each headline. Instead, for 15 experiments we have out-of-sample ratings of the average accuracy of each headline (e.g., from pre-tests, or from other experiments or conditions where participants made accuracy ratings rather than indicating sharing intentions). Thus, to assess the relationship between effect size and perceived accuracy, we conduct a headline-level analysis for each of these 15 experiments. Specifically, we correlate each headline’s out-of-sample perceived accuracy with the average treatment effect for that headline (sharing in treatment minus sharing in control). Consistent with our proposed mechanism, the treatment effect is strongly correlated with perceived accuracy in all experiments (Fig. 4): the meta-analytic estimate of the correlation is r = 0.773, z = 19.417, p < 0.001, and the magnitude of that correlation does not vary significantly across experiments, Q(14) = 18.99, p = 0.165. To provide an additional visualization of this relationship, in Fig. 5, we pool the data across all experiments and plot the perceived accuracy and treatment effect for every headline from each experiment (weighted by sample size, r(355) = 0.663, p < 0.001).

Meta-analytic estimate (via random effects meta-analysis) of the item-level correlation between the accuracy prompt effect on sharing and the headline’s out-of-sample perceived accuracy rating. The correlation coefficient and 95% confidence interval are shown for each study, and the meta-analytic estimate is shown with the red dotted line and blue diamond. We find no significant heterogeneity in effect size across studies, Cochran’s Q test, Q(14) = 18.99, p = 0.165 (k = 15 independent studies).

For each of the 357 headlines in the 15 experiments where out-of-sample accuracy ratings were available, the accuracy prompt effect (sharing when treated minus sharing in control) is plotted against the headline’s perceived accuracy. False headlines are shown in green, true headlines in orange. Dot sizes are proportional to sample size. Best-fit line and 95% confidence interval are shown.

Next, for the experiments using political headlines, we ask whether the accuracy prompts are differentially effective based on whether the headline is concordant or discordant with the participant’s partisanship. Right-leaning headlines are classified as concordant for Republicans and discordant for Democrats; the opposite is true for left-leaning headlines. We find that the accuracy prompts are significantly more effective for politically concordant headlines (three-way interaction between treatment, headline veracity, and political concordance; meta-analytic estimate b = 0.015, z = 3.124, p = 0.002), likely because people are more likely to share politically concordant than discordant headlines at baseline (meta-analytic estimate b = 0.102, z = 11.276, p < 0.001). Interestingly, baseline sharing discernment does not differ significantly for politically concordant versus discordant headlines (meta-analytic estimate b = 0.007, z = 1.085, p = 0.278).

We also ask whether there is evidence that the treatment effect decays over successive trials. For eight experiments (A through H), the order of presentation of the headlines was recorded; four studies had 20 trials, three studies had 24 trials, and one study had 30 trials. Examining the three-way interaction between headline veracity, treatment dummy, and trial number, the meta-analytic estimate (with a total of N = 10,236 subjects) is not statistically significant, b = −0.001, z = −1.869, p = 0.062. To the extent that there is some hint of a 3-way interaction, this is driven entirely by the first few trials. For example, when excluding the first four trials, the meta-analytic estimate of the 3-way interaction is b = −0.000, z = −0.292, p = 0.770 (indicating no significant order effect); and the overall treatment effect on discernment when excluding trials 1–4, b = 0.045, z = 4.188, p < 0.001, is very similar to the overall treatment effect on discernment when including all trials, b = 0.047, z = 4.804, p < 0.001. (The treatment effect on discernment in trials 1–4 was slightly larger, b = 0.065, z = 5.707, p < 0.001.) Similar results are observed when excluding the first five, six, seven, etc. trials; or when restricting to only the Evaluation treatment. Thus, we find evidence that the treatment effect persists at least for the length of an experimental session.

Individual-level differences

We now ask how the accuracy prompts’ effect on sharing discernment varies within each experiment, based on individual-level characteristics. To help contextualize any such differences, we also ask how baseline sharing discernment in the control varies based on each individual-level characteristic. Furthermore, because the distribution of the individual-level variables is extremely different for samples from MTurk (which makes no attempt at being nationally representative) versus the more representative samples from Lucid or YouGov (see Supplementary Information, SI, Section 1 for distributions by pool), we conduct all of our individual-level moderation analyses separately for Lucid/YouGov versus MTurk – and in our interpretation, we privilege the results from Lucid/YouGov, due to their stronger demographic representativeness. The results for all measures are summarized in Table 3.

We begin with demographics, which are of broad interest for misinformation research because differences in effectiveness across demographic categories has important implications for the targeting of interventions. With respect to gender, we find no significant moderation in either the more representative samples or MTurk. Interestingly, women are significantly less discerning in the control condition on MTurk, but not in the more representative samples. With respect to participants who identified as white versus other ethnicity or racial categories, we also find no significant moderation in either set of subject pools, and no significant differences in baseline discernment. With respect to age, we find that the accuracy prompts have a significantly larger effect for older participants in the more representative samples but not MTurk, while older participants are more discerning in their baseline sharing on both platforms (we find no evidence of significant non-linear moderation by age when including quadratic age terms). With respect to education, we find in both sets of samples that the accuracy prompts had a larger effect for college educated participants, and that college educated participants were more discerning in their baseline sharing. Importantly, however, the accuracy prompts still improve sharing discernment even for non-college educated participants (Lucid/YouGov, b = 0.033, z = 4.940, p < 0.001; MTurk, b = 0.059, z = 3.404, p = 0.001).

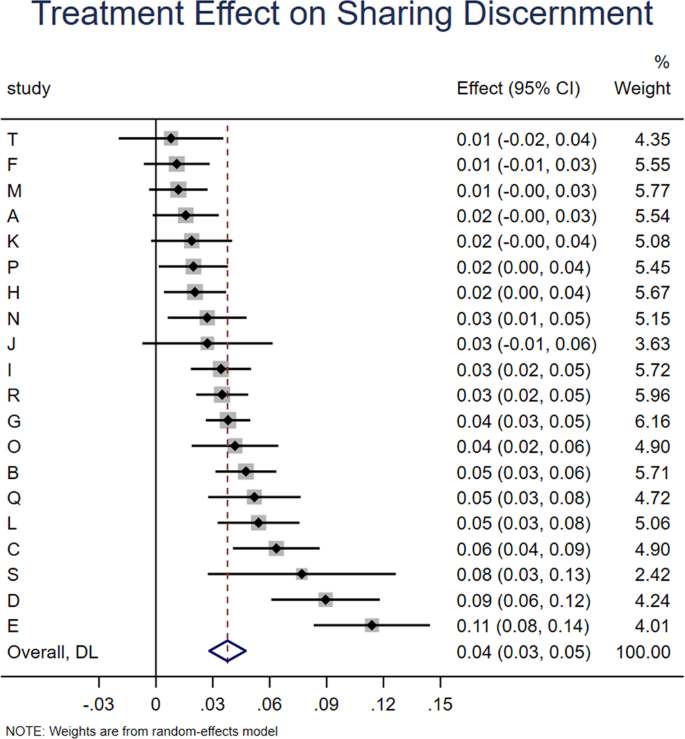

Next, we turn to political orientation (see Fig. 6). We find no significant moderation of the accuracy prompt effect by conservative (relative to liberal) ideology, either in the more representative samples or on MTurk. Importantly, we do find a significant negative relationship between conservatism and baseline sharing discernment (i.e., overall quality of news that is shared) in the control, and this is evident in both sets of subject pools (although the relationship is twice as large in the more representative samples). This worse baseline discernment aligns with real-world sharing data where conservatives were found to share more fake news on Twitter10 and Facebook12. This suggests that the lack of moderation by conservatism is not due to potential limitations of our conservatism measure.

Shown is sharing discernment in the control (red triangles) versus treatment (blue circles) as a function of liberal versus conservative ideology. The model fits for discernment in control and treatment, based on meta-analytic estimates of model coefficients, are shown with solid lines. The meta-analytic estimate of discernment in control and treatment at each level of conservatism (rounded to the nearest 0.25) are shown with dots. More representative samples from Lucid and YouGov are shown in the left panel; convenience samples from Amazon Mechanical Turk are shown in the right panel.

To shed further light on the potential moderating role of ideology, we also re-analyze data from a Twitter field experiment24 in which an overwhelmingly conservative set of users who had previously shared links to Breitbart or Infowars – far-right sites that were rated as untrustworthy by fact-checkers41 – were prompted to consider accuracy. Note that users’ ideology had been estimated based on the accounts they follow42, but moderation of the treatment effect by ideology was not assessed previously. Critically, the pattern of results for this Twitter data matches what we report above for the survey experiments: Users who are more conservative shared lower quality information at baseline, but we do not find evidence that ideology moderated the effect of the accuracy prompts. See SI Section 3 for analysis details.

Returning to our meta-analysis of the survey data, as a robustness check we also consider partisanship, rather than ideology, using three binary partisanship measures (preferred party, party membership excluding Independents, and having voted for Donald Trump in the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election). In the more representative samples, across all three measures we find that people who identify as Republican were significantly less discerning in their baseline sharing (in line with what has been observed previously), but partisanship does not significantly moderate the accuracy prompt effect on discernment. On MTurk, we see the opposite pattern: Republicans were not significantly less discerning in their baseline sharing, yet partisanship does significantly moderate the accuracy prompt on discernment, with the prompts working less well for Republicans (although the prompts still significantly increase sharing discernment among Republicans on MTurk, however defined: participants who prefer the Republican Party, b = 0.037, z = 2.988, p = 0.003; participants who identify with the Republican Party, excluding Independents, b = 0.035, z = 2.790, p = 0.005; participants who voted for Trump in 2016, b = 0.032, z = 2.608, p = 0.009; similar patterns are observed with only considering the Evaluation treatments, see SI Section 3). Although we have comparatively low power for statistically analyzing heterogeneity across studies (16 to 20 studies, depending on the individual difference), for completeness in SI Section 5, we report the results of meta-regressions predicting moderation using platform type, news type, and baseline discernment. The difference across platforms in the moderating effect of partisanship on the treatment effect was significant for people who voted for Trump versus those who did not (p = 0.033), marginally significant for participants’ preference for the Democratic versus Republican party (p = 0.078), and not significant for Democratic versus Republican party membership (p = 0.198); although these results should be interpreted cautiously in light of low statistical power.

The explicit (self-reported) importance participants placed on accuracy when deciding what to share did not moderate the treatment effect on sharing discernment in the more representative samples, but positively moderated the treatment effect on MTurk; and was positively associated with baseline sharing discernment in both types of subject pool.

When it comes to performance on the Cognitive Reflection Test, the more representative samples and MTurk show similar results. In both cases, participants who score higher on the CRT show a larger effect of the accuracy prompts, and are also more discerning in their baseline sharing. Nonetheless, the accuracy prompts still increase sharing discernment even for participants who answer all CRT questions incorrectly (more representative samples, b = 0.029, z = 2.784, p = 0.005; MTurk, b = 0.034, z = 2.119, p = 0.034; combined, b = 0.030, z = 3.581, p < 0.001).

Lastly, we examine the association with attentiveness in the 8 studies (all run on Lucid) that included attention checks through the study. An important caveat for these analyses is that attention was measured post-treatment, which has the potential to undermine inferences drawn from these data43. Keeping that in mind, we unsurprisingly find that the accuracy prompts had a much larger effect on participants who were more attentive, and that more attentive participants were more discerning in their baseline sharing. In fact, we find no significant effect of the accuracy prompts on sharing discernment for the 32.8% of participants who failed a majority of the attention checks, b = 0.007, z = 0.726, p = 0.468, while the effect is significant for the 67.2% of participants who passed at least half the attention checks, b = 0.039, z = 4.440, p < 0.001.